What I Learned Trying to Build a Scalable Dashboard Framework

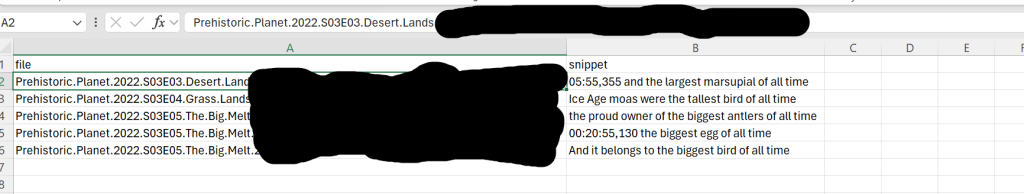

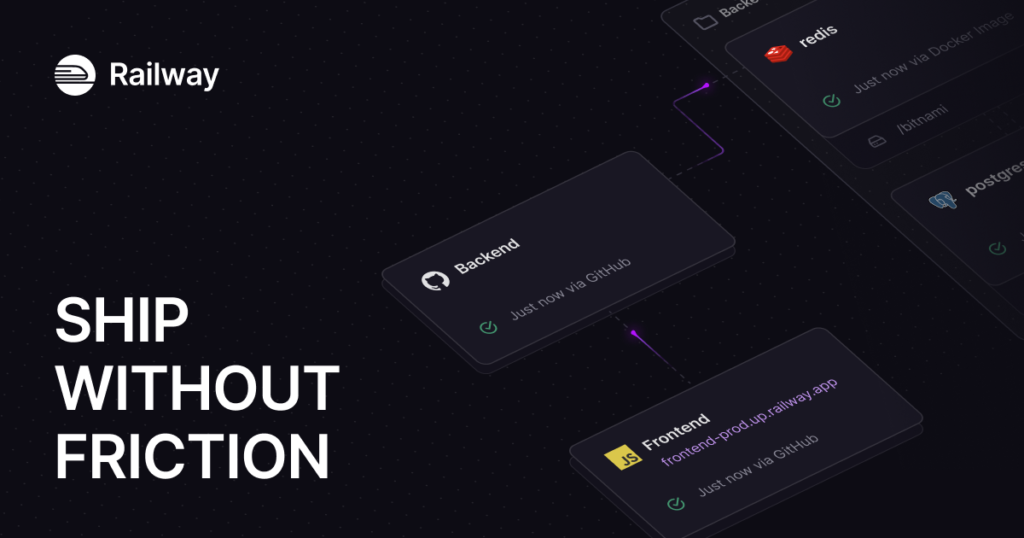

The goal of this phase of RewindOS was straightforward: design a scalable ingestion layer capable of tracking fandom signals in near-real time. In practice, that meant building a lightweight FastAPI service, backing it with PostgreSQL, and deploying it on Railway to validate whether the architecture could support future dashboards at low operational cost.

As a concrete test case, I wanted to monitor Reddit discussions around Star Trek: Starfleet Academy—specifically post velocity, controversy spikes, and narrative drift across subreddits. The idea was to ingest posts and metadata, normalize them into Postgres, and surface them as cultural “signals” alongside IMDb and news data.

What I didn’t fully appreciate—despite knowing it abstractly—was just how aggressively Reddit now enforces its platform boundaries.

Reddit’s API and the End of Casual Scraping

Reddit has effectively closed the door on nearly all casual or semi-legitimate scraping workflows. API access is tightly gated, application approval is slow and opaque, and even read-only endpoints are heavily rate-limited or restricted by OAuth scope. Anonymous access, once tolerated at low volumes, is now unreliable at best.

Beyond the API, Reddit’s cybersecurity posture is formidable:

- Bot detection at the edge (behavioral + fingerprinting)

- Aggressive IP and ASN-based throttling

- User-agent and request-pattern heuristics

- Inconsistent but intentional JSON endpoint breakage

In short: the platform is designed to detect intent, not just volume. Attempting to build a scraper to monitor Star Trek Academy posts wasn’t just blocked—it surfaced how mature Reddit’s anti-extraction infrastructure has become. I knew this intellectually, but putting it to the test made the reality clear: Reddit data is no longer a “free signal layer” for independent researchers.

Infrastructure Takeaways: Railway and PostgreSQL

On the infrastructure side, the experiment was still valuable. Railway proved viable for rapid prototyping: fast deploys, sane defaults, and painless Postgres provisioning. It’s not magic, but for early-stage dashboards and internal tooling, it removes a lot of friction.

PostgreSQL held up exactly as expected—flexible enough to store raw ingestion data, structured metrics, and future-proofed schemas for signals that don’t fully exist yet. The limitation wasn’t the database or the API layer; it was upstream access to the data itself.

The Bigger Lesson

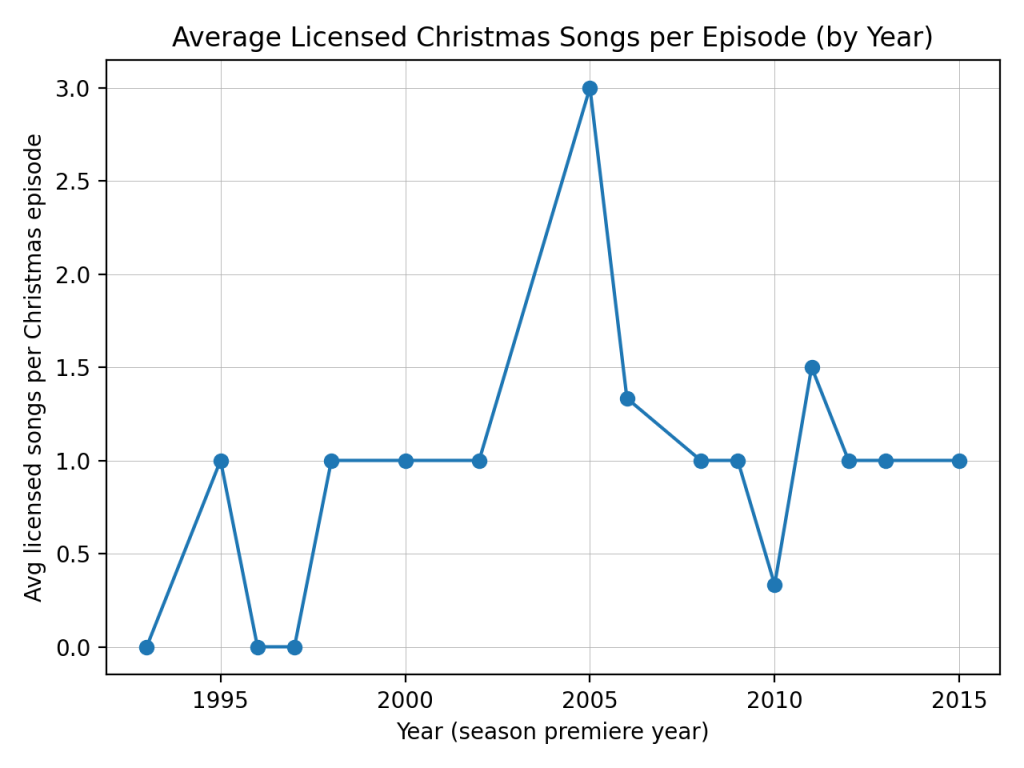

If RewindOS is going to measure cultural velocity, controversy, and fandom health, it can simply revert back to its original dashboards created using python and json. Though not real time it still paints a pretty picture about what’s going on within the fandom itself. Which is all we really care about.

What This First Pass Shows

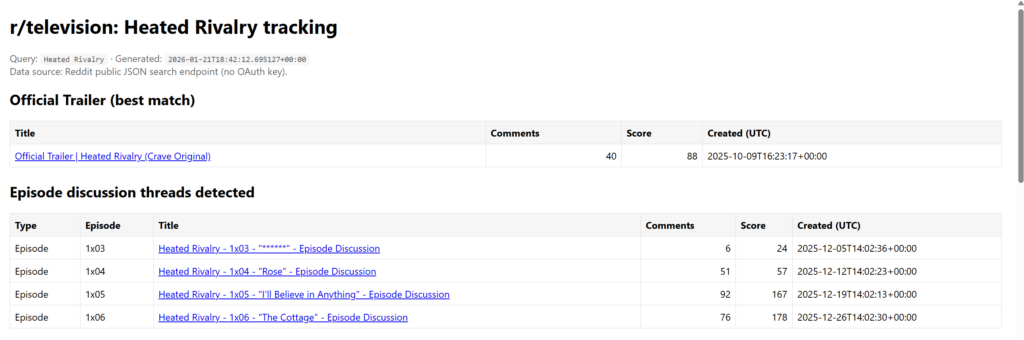

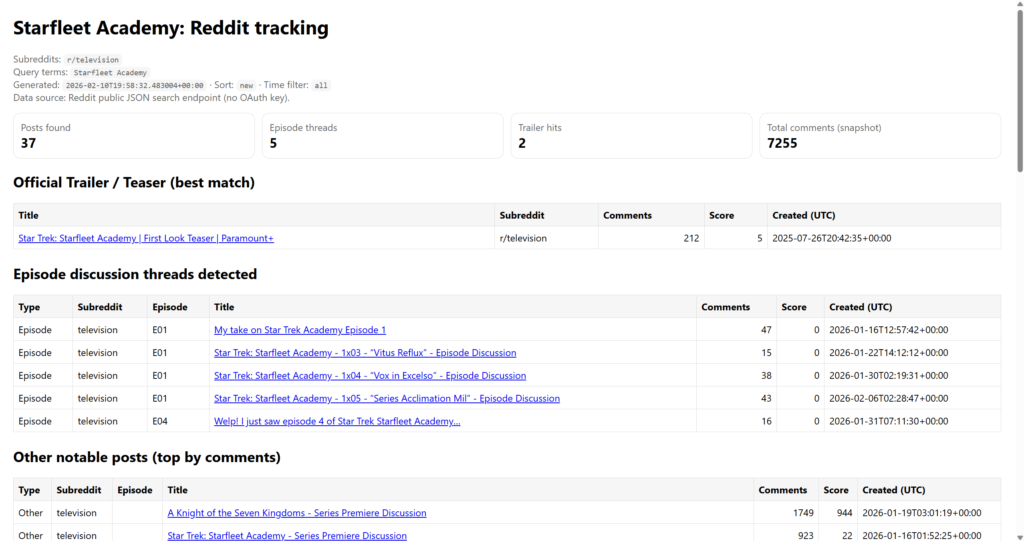

This first iteration of the Starfleet Academy trackers focuses on where conversation actually happens and what kind of attention the show receives, rather than trying to simulate a live social feed.

A few clear patterns emerge immediately:

1. r/television captures cultural moments, not fandom

The r/television tracker surfaces:

- Trailers and first-look teasers

- Series premiere threads- official discussions again did not occur on r/television until the second week

Engagement here is highly concentrated:

- One or two posts (trailers or premiere discussions) account for a large share of total comments.

- Topical discussions related to the show is sparse and fragmented

This tells us r/television is best read as a general-audience and industry sentiment signal, not a place where sustained episode-by-episode engagement lives. However, the moderators do seem to be doing a good job keep the sub from being bombarded by the larger cultural divisions within the Star Trek community related to this show as I will discuss below:

The absence of strong megathreads is itself a useful signal: it shows where not to look for fandom intensity.

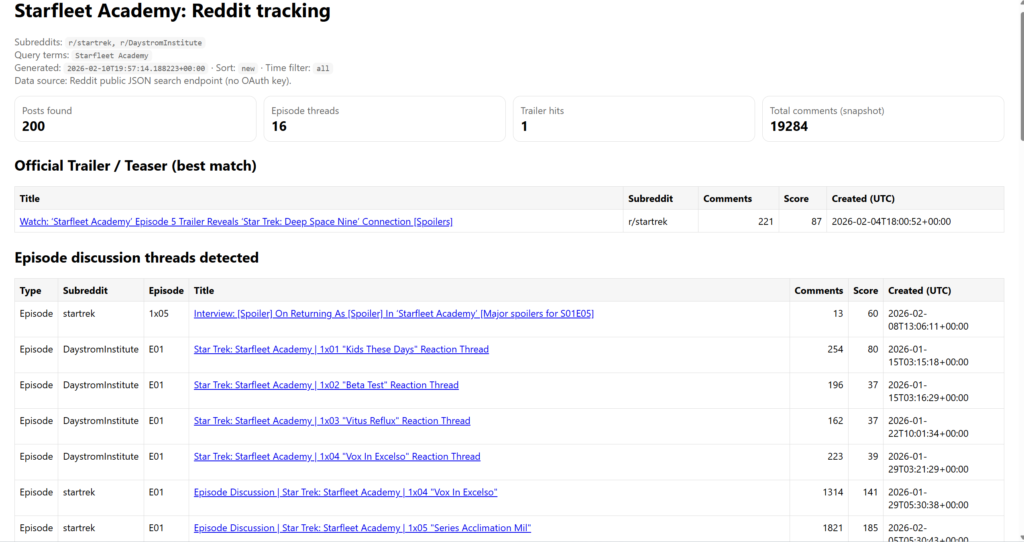

2. Adding Star Trek–specific subreddits changes the signal shape

Once r/startrek and r/DaystromInstitute are included:

- Overall engagement increases substantially

- Episode-level discussion becomes more structured

- Conversations shift from “Is this good?” to “How does this fit into canon / science / continuity?”

This confirms the need for separate dashboards rather than one blended feed.

What this Tracker Looks At

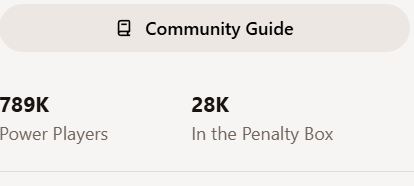

Star Trek Subreddits Tracker Focus

The second tracker (r/startrek + r/DaystromInstitute) is intentionally different.

It shows:

- Sustained episode-to-episode discussion

- Canon, timeline, and science-based analysis

- Deep engagement that doesn’t show up in mainstream spaces

r/DaystromInstitute, in particular, acts as a high-signal, low-noise environment:

- Fewer posts

- More thoughtful, analytical comments

- Less reactionary churn

This tracker is closer to a fandom depth and intellectual engagement index.

In general it does appear that interest in the cultural hate of SFA at least on reddit has decreased and comments and engagements are ticking up.

The show while currently sitting with a horrible 4.3 IMDB rating gets more engagement than other one off streaming shows and there is some discussion among fans who had watched the latest Sisko-themed episode of SFA but claim will not watch any of the others (unless I am assuming there are further ties to Star Trek canon – in their eyes.)

It remains to be seen if there will be any changes to the Star Trek Starfleet Academy schedule, but despite the supposedly low rating these engagements may be what Paramount is looking for after all.

If you want to see or run the Python script used for this analysis, the full repository is here:

👉 GitHub: